Back to the book I never wrote - the one about good protesters, bad protesters, governments and terrorists...

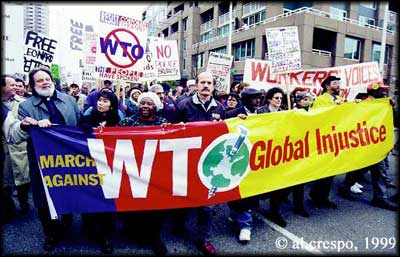

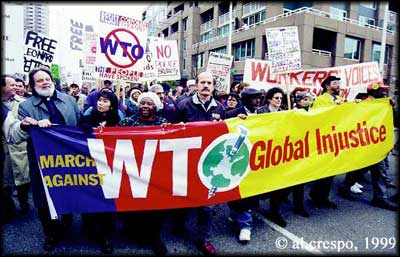

In the discussion on my post from a couple of weeks ago, Tim reminded me of the (in)famous protests at the WTO meeting in Seattle in 1999:

In the discussion on my post from a couple of weeks ago, Tim reminded me of the (in)famous protests at the WTO meeting in Seattle in 1999:

The only thing I remember of it is images of chaos, tear gas, bandaned young people throwing rocks, police behind barricades, fires, looting (I may be adding that now to the memory). It was a series of clips which spoke of danger, chaos, anarchy, etc.

Did it happen? Yes.

Did it come close to describing what the majority of people who were at the protest wanted to be seen and heard? My guess is, probably not. But it made for good sound and video bites.

Part of what drew me into trying to write about events like this is that, as a journalist, I felt the news media were peculiarly bad at handling them - and I was both fascinated and troubled by the way this interacted with the agendas of politicians and different groups of protesters.

The Gleneagles summit was the second time the G8 leaders had met in the UK since New Labour came to power. The fact that they met this time in the wilds of Scotland rather than in a major city was a reflection of the bandwagon of international protests, for which the Seattle WTO is often seen as the starting point. However, for the Blair government, there was also the memory of the 1998 summit in Birmingham - where their media managers were wrong-footed by the scale of public protest.

I remember arriving that day with a seasoned activist, a veteran of the anti-road building and Reclaim The Streets protests of the 1990s, who was simply gobsmacked by the coachload after coachload of ordinary people who had turned up to picket the world leaders - 70,000 of them formed a human chain around the city centre. This was the work of Jubilee 2000, a campaign for the cancellation of third world debt (which my School of Everything colleague Paul Miller helped organise), which did an outstanding job of raising consciousness of global injustice and mobilising a new constituency of protesters, many of them white-haired churchgoers, through an alliance of mainstream charities and campaign groups. Ann Pettifor, the campaign's founder, has written about the impact this had on the summit:

In what we thought of as a calculated move to de-mobilise our supporters, (but which they argued was just a security measure) the Foreign Office had made a surprise announcement the Tuesday before: G7 leaders would not be in Birmingham on Saturday 16th...

And so it was, that on the day, at 11 a.m. Birmingham was brimming with 70,000 peaceful, cheerful Jubilee 2000 campaigners, their banners and posters. Present also, were about 3,000 journalists, sent to cover the event. Only the G7 leaders were absent, giving the journalists very little to write about. So naturally they turned to the demonstrators. Overwhelmed by calls from hacks, we had done dozens of interviews by 11 a.m. It did not take long for No. 10’s spin doctors to realise that a major strategic error had been made. Soon the call came. The Prime Minister, Tony Blair, was flying back from the country-house meeting earlier than expected. Would it be possible to meet with Jubilee 2000’s leaders?

Given New Labour's permanent anxiety about controlling the media agenda, it is easy to imagine that avoiding any such strategic errors came high on the agenda in the planning of the Gleneagles summit. And so, months beforehand, a strategy seems to have been adopted to polarise activists into two apparently antithetical camps - the good protesters and the bad protesters. This was spelt out by Blair himself, in a newspaper interview in March 2005 (republished on Indymedia):

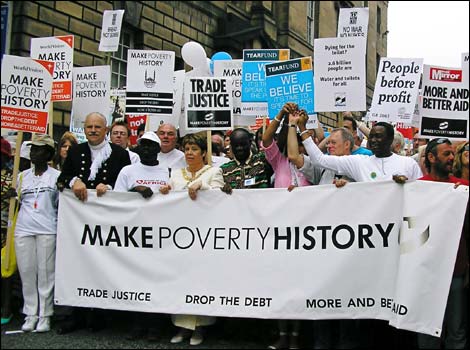

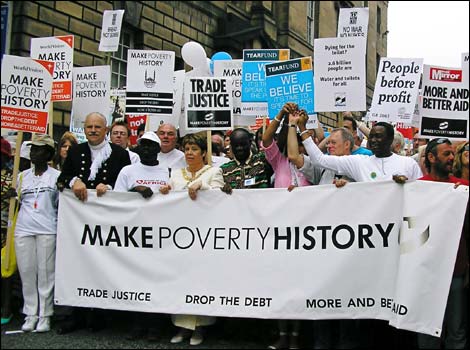

It would be very odd if people came to protest against this G8, as we're focusing on poverty in Africa and climate change. I don't quite know what they'll be protesting against... There will be people who come out on the street in favour of the Make Poverty History campaign and that's a good thing.

This strategy was at once reasonable-sounding and dangerous - dangerous, because all legitimate, non-violent, "good" protesters are represented as supporters of the government, while all opposition becomes associated with violence, irrationality and illegitimacy. (In the same interview, Blair told the reporter he "couldn't rule out" using recently passed anti-terrorist laws against anti-G8 protesters.)

On the ground, for anyone looking for more than a soundbite, it was obvious that this black-and-white polarisation didn't hold. There was a spectrum of dissent, of deep concern and anger at the consequences of the policies the G8 leaders represented, which ran from the white-clad Make Poverty History marchers through the various shades of red and green and no particular colour, to the black bloc anarchists at the other end.

However, the effectiveness of the government's media management was reinforced by journalists' desire for simple, black-and-white narratives.

One measure of its success was the BBC's uncritical presentation of the Make Poverty History campaign and the Live 8 concerts. This was the subject of an official report just this week, which acknowledged that:

the BBC’s involvement with Make Poverty History in 2005 presented challenging dilemmas and was, for some, a difficult experience... there remain, even now, scars which have not fully healed.

Libby Purves, herself a well-known BBC presenter, expresses this discomfort more explicitly:

Personally, I applaud the nerve and passion of [campaign organisers] Geldof and Curtis, but not the BBC’s massive loss of perspective over Live 8. Carried by the vastness and suddenness of the enterprise... senior management rolled over whenever the campaigners – backed by Gordon Brown – pushed. Valid scepticism about Live 8’s demands was ignored. Even when Geldof arrogantly told Paul Martin, the Canadian Prime Minister, he was “not welcome” at the G8 summit unless he obeyed, the BBC continued presenting the event as uncritically as a Prom. It was all very uncomfortable and clearly won’t be allowed to happen again.

What Purves doesn't highlight is the way uncritical representation of the "good protesters" compounded the false polarisation of that wider spectrum of protest.

I spent the day of the Edinburgh march reporting for Make Poverty History Radio - a temporary station with no need for impartiality! But towards the end of the afternoon, I remember ducking into a pub a few streets away to catch some of the BBC coverage. As I watched, they cut from a helicopter view of a small group of black bloc kids penned in by riot police, to a reporter striding side by side with a group of marchers, chatting away to them. Whatever the exigencies of covering such an event, the contrast between the two shots - the embedded reporter with the "official" protesters, the aerial view of the trouble-makers - told its own story, one which chimed with much of that week's coverage.

There are various reasons why the unoffical protesters seldom get a hearing for their side of the story. Some of it has to do with their own suspicion and sometimes hostility towards the mainstream media, and the fact that they often become visible only when a minority start smashing windows. Some of it has to do with journalists' preference for talking to people their audience can identify with or who they themselves feel comfortable around. One big piece in the puzzle, though, is the relationship between the police and the media.

In the ordinary course of news reporting, the police are a privileged source of information. So much of the daily news agenda is made up of crime stories, court reports and other situations in which the police speak with authority. As a rule, you don't see interviewers challenge police officers the way they challenge politicians. This is just how things work, and while not always perfect, it's hard to think of an alternative.

The problem comes, though, when the police become one side of a story. Protests which don't have the endorsement of the authorities are a feature of democracy - a situation in which you can only protest with the government's permission is undemocratic. But such protests are often the scene of confrontations in which the police play a role - sometimes on their own initiative, sometimes on political orders - which is worthy of journalistic questioning. On the whole, however, this is not recognised, and it is common practice for the police version of events to be reported with the same uncritical attitude as in a crime story. (One TV reporter told me how his copy was rewritten to tally with a police press release, with the effect that shots of an activist being beaten by police were accompanied by a newsreader's description of "violence by protesters".)

For activists who see themselves misrepresented, it is easy to buy into conspiracy narratives about the forces which control the media. In my experience, what actually goes on is slipperier and less driven by intentions, though the effect may sometimes look like a conspiracy.

But there are at least two good reasons why anyone who wants to change the world should avoid conspiracy narratives. One is that if you believe them, you might as well give up - since the logic of the conspiracy narrative involves imputing such overwhelming power and capacity for control to the state/the multinationals/the 12ft-high lizards. The second reason is that, if you attribute your failures to conspiracies against you, you're unlikely to engage in the kind of reflection that gives you a chance of achieving more next time round.

The time I spent hanging out with anti-globalisation activists and getting involved with those campaigns was incredibly inspiring, as well as (sometimes) deeply frustrating. Whatever else, it challenged me to do something more constructive with my life than working as a mainstream news reporter. And, while I never got that book published, the process of writing allowed me to think through how you turn good intentions into making a real difference for people's lives - which certainly contributed to what I'm doing now.

But more on that in a future post...

I fully intend to carry on the conversation I've been having with Tim on my

I fully intend to carry on the conversation I've been having with Tim on my